- Solitary bees

- Creating homes for Solitary Bees

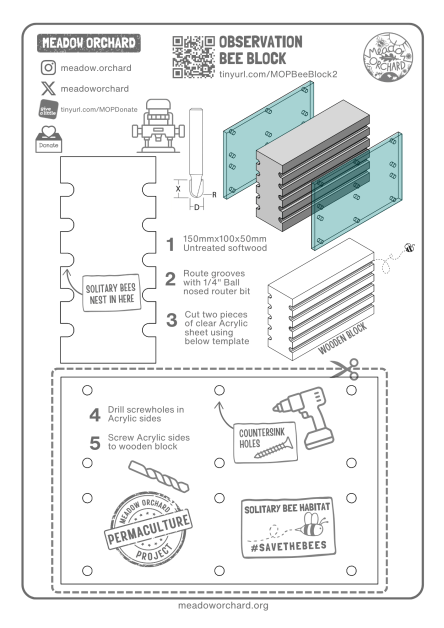

- Bee hotels with a view

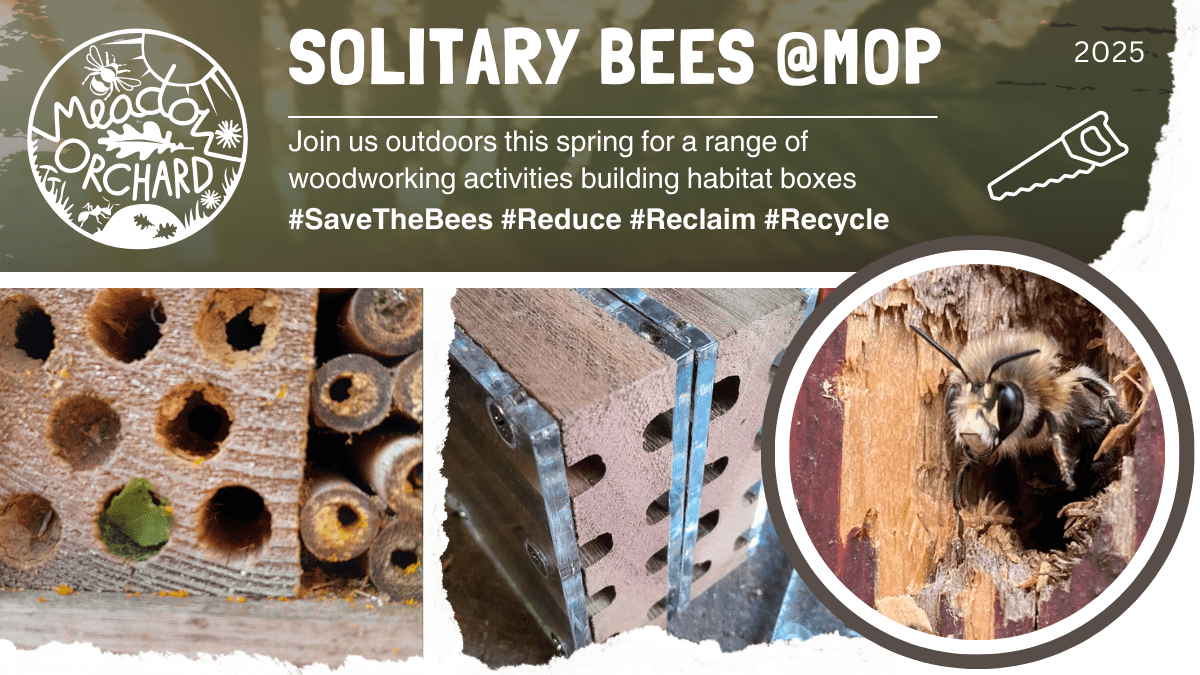

- Getting involved

- Bee hotels or Bug houses?

- It doesn’t work, I don’t have any bees!

- Solitary Bee Parasites

- Solitary Bee Lifecycle

Solitary bees

There are around 270 species of bee in the UK, 24 of these are bumblee bee species, along with honey bees, solitary bees provide the remainder. Honeybees (Apis Mellifera) over winter as adults, feeding on a reserve of honey to sustain them when there isn’t any pollen and nectar sources to feed.

Solitary bees don’t live in a colony and produce honey like honeybees. Instead, female solitary bees create nests in plant stems, cracks in trees, or other sheltered spots. They lay eggs in these nests and fill them with pollen and nectar to feed the larvae. After the eggs hatch, the bees overwinter as pupae and emerge as adults the following spring.

The adult solitary bees only live for about four to six weeks, depending on the species. During this time, they mate, lay eggs, and complete the cycle. Though they live short lives, solitary bees play an important role in pollinating plants, especially in early spring.

Creating homes for Solitary Bees

It’s easy to create habitat for solitary bees, and solitary bees readily take up nest in these kinds of structures. A bundle of hollow plant stems such as reed or bamboo can be tucked away undercover, under the roof of a porch is ideal or under the overhang from a shed roof.

Ideally the nest site should receive some sun during the day, be protected from prevailing winds and located around shoulder height. If the habitat is located close to the ground it will get splashed by rain and will probably become more of a habitat for spiders and ground beetles rather than bees.

You can also drill a number of holes in a tree round, log, or offcut of untreated fence post. Simply fix the post or tree round to a wall or fence post to raise it from the ground. When drilling holes its a good idea to drill them at a slight angle so if any prevailing rain enters the holes it will tend to drain out towards the opening. The holes shouldn’t really be drilled all of the way through the log or post as this will make the nests more prone to parasites. It’s a good idea to use a long pattern drill bit, around 150mm for leafcutter bees and shallower for smaller bee species such as Mason Bees and Orchard Bees.

Bee hotels with a view

We are currently building a number of these bee habitat blocks with viewing windows! These will enable a fascinating view into the nest building and lifecycle of Leafcutter bees and Red Mason bees (Osmia Bicornis).

Getting involved

If you’d like to come along to Meadow Orchard this Spring, help out with some woodwork, learn how to use a range of tools, please send us an email or use the link below to Sign-up for more info!

Bee hotels or Bug houses?

Is it a house, is it a hotel, do bees live in them, are bees bugs? Well no, not really, but we don’t really mind what you like to call the haitat boxes, the important part is that you are providing habitat!

It doesn’t work, I don’t have any bees!

Bees will chose their nest sites around forage and existing habitat. They may come immediately or take longer to discover the nest sites. Just because bees aren’t using it, other insects, bugs, lacewings, ladybirds, spiders and birds will use the boxes as shelter or spaces to feed.

Solitary Bee Parasites

The word parasites often has negative connotations however in nature there is a place for everything and everything in it’s place. Parasites help to keep populations in check and maintain a balance. Parasites of solitary bees even include other solitary bees such as the Cuckoo bees. The larvae of Cuckoo bees have evolved special mouth parts so that when the larvae emerges from it’s egg (laid inside the nest of another bee), the larvae can kill and eat the other larvae! The lifecycle on the Ichneumon wasps, another parasite of solitary bees is truly fascinating (if somewhat akin to the film Aliens!).

When creating wildlife habitat, it’s always a good idea to create a number of habitat boxes in different locations, rather than all in one place. Creating a diversity of sites helps ensure bees have access to habitat in the best possible location and will choose accordingly. It’s also best to avoid a huge habitat box or structure rather than a number of smaller ones. A megacity bug house or bee hotel can mean that it’s easier for parasites to parasitize the whole lot in one go!

Solitary Bee Lifecycle

The Willughby’s leafcutter bee (Megachile willughbiella) is a species of leafcutter bee known for its unique nesting and reproductive behaviour. Here’s a general outline of their lifecycle:

- Egg Stage:

- Female leafcutter bees lay eggs inside cavities, often in hollow stems, wood, or pre-existing holes in structures.

- The female bee cuts leaves from plants and uses them to line the nesting cavity. These leaves are rolled into “discs” that are placed in the cell, forming a kind of cell in which the bee lays a single egg.

- The female bee gathers pollen and nectar and fills the remaining space in the cell to provide a food source for the larva when it emerges.

- The bee then seals in the cell with a door made from discs of leaves. The bee pulps the edges of the leaves, mixing with its saliva to bond them to the edges of the hole. This ensures that the cell is protected from the weather over winter.

- Up to thirty of forty leaf discs are used for each nest.

- As the nest chambers are filled up the female bee will lay fertilised eggs. This means that the first bees to emerge in the spring are males. The males will then fly away in search of other female bees. This helps to ensure that the DNA will be spread over a larger area as the males will mate with bees from a wider area.

- Often the last cell the female bee creates will be left empty. This helps to prevent the bees falling victim of parasites such as Ichneumon wasps. The long ovipositor of the wasp can only reach as far as the first cell in the holes populated by the solitary bee.

- Larval Stage:

- After the egg is laid, it hatches into a larva.

- The larvae feed on a provision of pollen and nectar that the female bee has placed inside the nest.

- Once the larvae has consumed the food supply it then begins the pupal stage of it’s lifecycle.

- Pupal Stage:

- Once the larva is fully developed, it enters the pupal stage.

- In this stage, the larva undergoes metamorphosis to become an adult bee. The pupal stage is spent in the safety of the nest, within the leaf-lined cell.

- The pupa will develop into an adult bee, emerging fully formed the following spring, around April.

- Adult Stage:

- After the pupal stage, the bees emerges as adults.

- Once the weather warms up to bees will begin to emerge. This isn’t such an easy task, the bee will have to gnaw it’s way through up to 30 layers of leaves, enlarging the hole so it’s large enough to squeeze through! Upon emerging the bees will flying away to mate or begin their own nesting cycle.

- Adult bees are responsible for pollination and for cutting leaves to construct new nests for the next generation. Although the bees damage leaves, they only cut small sections from leaf which isn’t sufficient to impact the health of the plant. The circular cutouts are a good indication that you have leafcutter bees nesting nearby.

- Mating:

- Adult males may mate with females as they leave their nests. After mating, the female will begin the process of nesting for the next generation.

Leafcutter bees, including Megachile willughbiella, typically complete one or two generations per year, depending on environmental conditions and food availability.

The lifecycle emphasizes the bee’s reliance on specific plant resources (leaves) for constructing their nests, as well as their role in pollination.

You must be logged in to post a comment.