- Exploring the Geology Beneath Our Feet

- A Roman Legacy at Highgate Wood

- What Do We Mean by “Clay”?

- The Character of London Clay

- Comparing Highgate Wood and Meadow Orchard Clays

- From Clay to Sand: The Bagshot Formation

- Water, Ice, and Time

Exploring the Geology Beneath Our Feet

Our recent collaborations with potters Amy & Shem at the nearby Turning Earth studios have sparked exciting conversations around local geology—particularly in relation to clay from Highgate Wood, Queen’s Wood, and our own source at Meadow Orchard. These exchanges have highlighted fascinating overlaps between pottery and the unique geological history of North London.

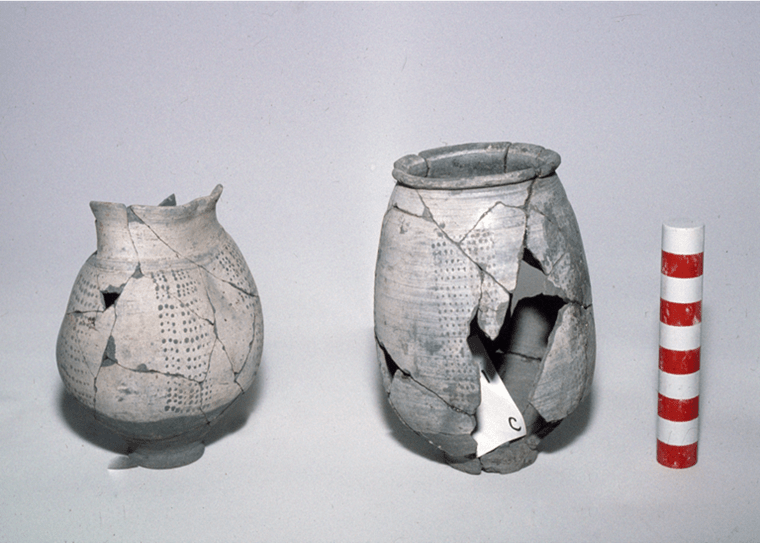

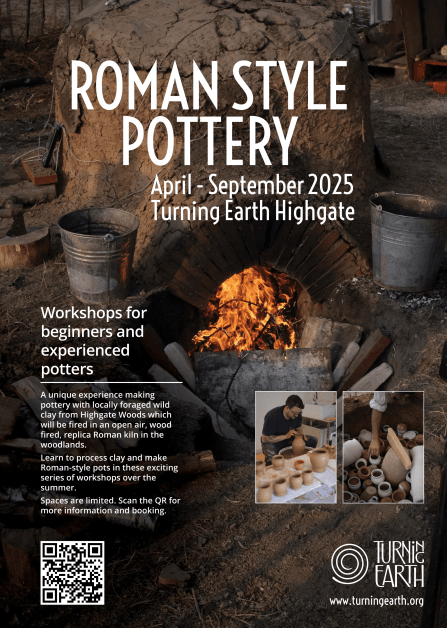

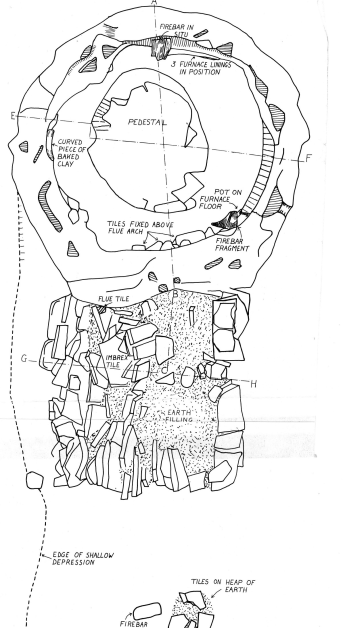

A Roman Legacy at Highgate Wood

Highgate Wood was once the site of a bustling Roman pottery between AD 50 and AD 160, following the Roman conquest of Britain in AD 43. But what made this location so suitable for pottery production and why isn’t there a Roman Kiln at Meadow Orchard?

If you’d like to learn more about the history of the Highgate Wood Roman Kiln and even be a part of the next firing, Turning Earth studios are hosting a programme of events, building replica Roman pottery. To find out more, click the links below.

BBC Radio 3 New Generation Thinkers: Clay and Collapse

What Do We Mean by “Clay”?

While potters often refer to their material simply as “clay,” it’s rarely just that. Typically, it’s a mix of clay minerals, silt, and sand. To modify its properties, potters also add materials like grog (ground-up fired pottery) or sand. These additions improve workability and firing behavior—grog, for instance, provides strength and helps the clay withstand thermal stress in the kiln.

The specific composition of a clay body can determine whether it’s best suited for fine ceramics or more robust items like bricks and tiles.

The Character of London Clay

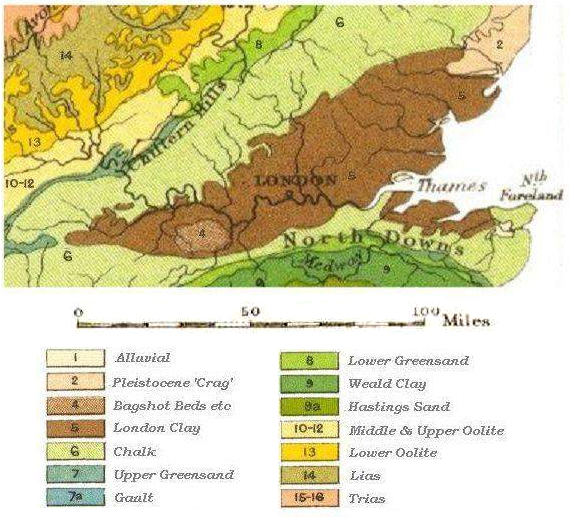

Much of North and Central London sits atop London Clay—a thick, uniform deposit laid down in a tropical sea around 50 million years ago. In some areas, it reaches depths of up to 100 – 150 meters. This stiff, consistent material helped enable the construction of the London Underground, the clay being an ideal tunnelling material. South London’s geology features more variable sands, silts, and clays of the Lambeth Group and Reading Formation, which provide more challenging conditions for tunnelling.

Over time, changing sea levels influenced the types of sediment deposited, resulting in variations in clay, silt, and sand content. These grains include quartz (ranging from angular to rounded), mica, pyrite, and gypsum.

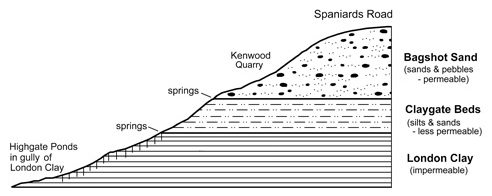

As we move upward through the layers of the London Clay Formation, the composition becomes coarser. The uppermost layer, known informally as the Claygate Beds, contains a higher proportion of silt and sand, making it particularly suitable for pottery.

Comparing Highgate Wood and Meadow Orchard Clays

The clay found in Highgate Wood—used by Roman potters and in the upcoming Replica Roman Kiln (AD 2025)—differs notably from the clay at Meadow Orchard. While Meadow Orchard clay reflects the more typical composition of deeper London Clay in the North London Basin, Highgate’s Claygate Beds offer a coarser, sandier blend that better lends itself to pottery production.

This upper layer forms a transition zone between London Clay and the overlying Bagshot Sands and has proven ideal for shaping and firing ceramic works.

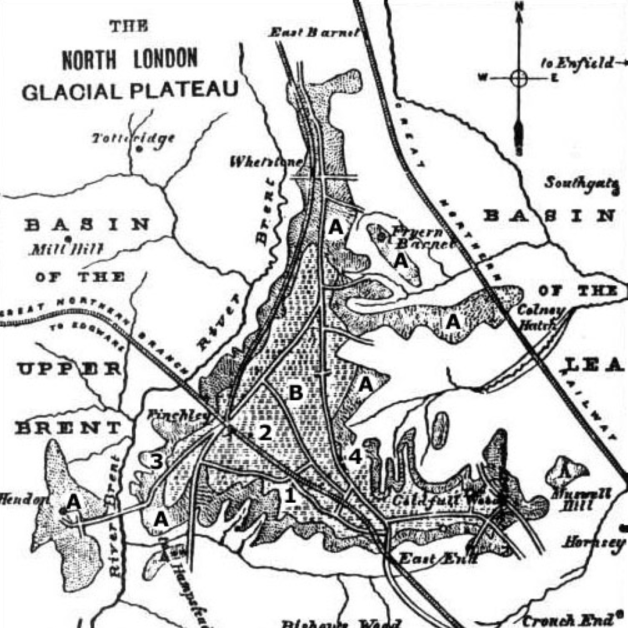

The Geological Backdrop: The London Basin

The London Basin is a large, roughly triangular sedimentary basin covering southeast England, including London, parts of East Anglia and leading to the North Sea. It is bordered by the Chiltern Hills to the north, the North Downs and Berkshire Downs to the south.

The basin was formed through tectonic activity that uplifted surrounding areas of chalk seabed, created a central depression. The resulting chalk formations, including those seen in the Chiltern Hills and North Downs, shaped the landscape and influenced subsequent sedimentation patterns.

From Clay to Sand: The Bagshot Formation

Around 50 million years ago, as the subtropical sea covering the London Basin began to shallow, sediment types shifted. Fine clays and silts gave way to coarser sands, which eventually formed the layer known as Bagshot Sand.

This sandy layer now caps some of North London’s highest elevations—such as Hampstead Heath—and extends eastward to form ridges in areas like High Beach and Loughton Camp in Epping Forest. Above the Bagshot Sands, a thin layer of pebbly gravel was deposited, some of which was historically quarried from small pits still visible today.

Water, Ice, and Time

Many of Epping Forest’s streams originate as springs, where water percolates through sand and gravel until it reaches the impermeable Claygate Beds beneath. During the Ice Age, glaciers brought with them Chalky Boulder Clay from the Chilterns. Between glacial advances, meltwater sculpted the land, and retreating floods left behind layers of sand and gravel.

The ancient Thames, much broader than it is today, carved its way deeper into the landscape with each fluctuation in sea level over the last 250,000 years—shaping the geology we see today across North London.

You must be logged in to post a comment.